Four years ago, I wrote about Ticket to Ride, a board game I had become “addicted to” during the pandemic. My article identified lessons from playing the game that could be applied to nonprofit leadership. (By writing about it, I could justify my addiction).

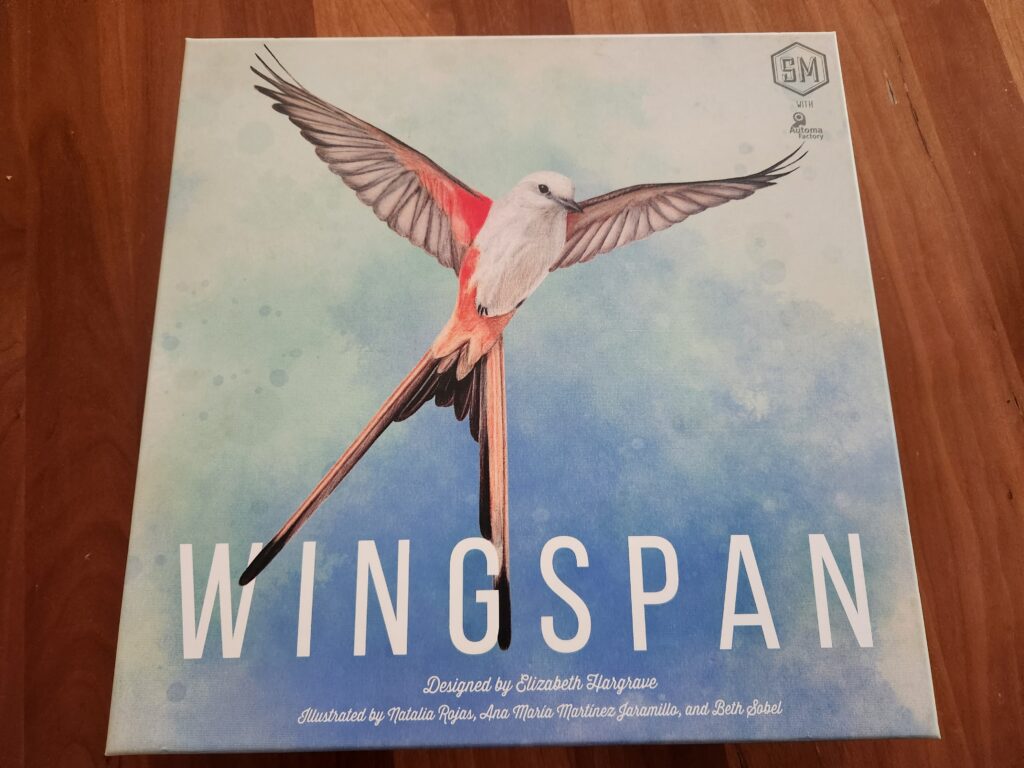

Now it’s time to share some overlapping lessons from another game that I’ve played a LOT in recent years, Wingspan.

In Wingspan, you compete with others to build the best wildlife refuge. (For my wildlife conservation clients, I know!!!)

To build your refuge, you collect different types of food, use them to play different birds, lay eggs on those birds, and then, over the course of the game, take actions associated with the different birds, based on the specific combination of birds you have in three habitats: forests, grasslands, and wetlands.

Here are six lessons from Wingspan that I feel nonprofits should consider. They overlap somewhat with my Ticket to Ride lessons, but with some crucial differences.

Lesson 1: Smaller impact/less effort is sometimes better at the start

The winner of the game is determined by a combination of ways to score points, perhaps the most important of which is the numerical value of the birds you’ve played. While it’s tempting to immediately play high point birds, lower point birds often are the ones that provide more resources to you when activated over the course of the game. (The higher point birds often just look pretty).

The nonprofit lesson, especially for those getting going: Don’t always go for the biggest impact right from the start. (See my recent blog and read the section about the impact/effort matrix). It’s often better to set in motion strategies that take less effort, for less impact, while building resources for a bigger play down the road.

Lesson 2: Search for synergies

In Wingspan, all the birds you play have powers. For example, one bird when activated may give you a worm. Another bird may let you permanently cache worms on a bird, which counts as a point at the end of the game. These birds have more value when played together than just one of them. It’s usually not the person who plays the “best birds” who wins, so much as the best birds that reinforce each other.

The nonprofit lesson: Look for synergies where work done to pursue one outcome also benefits another outcome. Perhaps your community education reinforces your advocacy work. Or the content you create for your email newsletter can also extend your social media reach. Or your advocacy work yields ongoing funding that provides future opportunities for advocacy.

Lesson 3: Focus on a few things

While it’s tempting to build really strong sets of birds in all three habitats (forest, grasslands, and wetlands), my experience is that focusing on just two yields a better result, as you can play more birds in those habitat that build upon each other when activated in succession. Not that you play zero birds in the third habitat – that rarely works – but focus that habitat on playing higher point birds.

The nonprofit lesson: Don’t try to do everything equally all at once. Pick one or two things to do really well and build out from there.

Lesson 4: Don’t chase shiny objects

The game has four rounds and each round has a unique goal that scores points, randomly picked from a large number of possible end of round goals. These are things like: number of eggs in the forest, or number of birds in the wetland, or number of brown-powered birds (a particular type). The randomness makes each game unique (or close to it). The end of round bonuses are large enough they can determine who wins so it’s important to pay attention to them. But they’re not THAT large. If you deviate too much from an otherwise strong strategy to win those end of round bonuses, you often come out worse off.

The nonprofit lesson: This is the equivalent of chasing money (usually from a foundation). It sounds great to get the grant, but if it’s for work that you wouldn’t otherwise want to do, it usually is a distraction from your mission and long-term strategy.

Lesson 5: Adapt to your opposition

There are special pink-colored birds that activate when another player takes certain actions. Think about the bird that lays its egg in another bird’s nest! Playing these pink birds can be very powerful. But that’s only true if you’re paying attention to the other player’s strategy to predict what they’re most likely to do. And if somebody else plays a pink bird early, you may wish to adjust your strategy to avoid benefiting them too much.

The nonprofit lesson: Particularly for advocacy organizations who may have organizations on the “other side” of whatever issue you’re focused on, you shouldn’t just ignore their expected opposition as you plan your activities. Are there things you expect them to do that you should prepare for ahead of time? Are there things you should avoid doing because it might boomerang back against you based on their reaction? What messages are they giving to elected officials and how should you adapt your message in response?

Lesson 6: Sharing is often the best option

Some birds when activated produce resources not just for yourself, but your opponents. Example: When activated, everyone gets a worm. Or everyone draws a new bird card. When I first started playing Wingspan, my competitive instinct took umbrage with playing these “sharing” birds. But over time I saw that the combination of the bird’s point value and the resources offered often gave me more value than my opponents, particularly if I could use other birds that took advantage of the resources. Also, when playing with the same opponents repeatedly over time, my willingness to play “sharing” birds increased the odds my opponents would do so, sending resources my way. When more players use these types of birds, overall scores tend to go up.

The nonprofit lesson: There are things you can do as a nonprofit that benefit you and other nonprofits with which you are sometimes competing (over funding, for example), but with whom you often collaborate (working to advance overlapping missions, for example). Sometimes the best thing to do is something that advances all the groups with whom you’re allied, even if you’re the one putting in the time/money to do it. Becoming known as an organization that plays well with others increases the odds you’ll be invited into sharing opportunities in the future, including from funders.

Fancy a game?

There you have it: six lessons for nonprofit leaders from playing Wingspan. I can now play the game more without feeling guilty. If anyone is playing it online and looking for an opponent, just email me and we can set up a game while chatting about how Trump is taking the country over the edge into fascist authoritarianism.